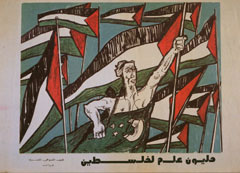

A Million Flags for Palestine

Artist: Unattributed (Egypt)

Publisher: The Communist Party of Egypt (CPE)

Circa 1948-52

The central graphic element in this poster is a bare-chested man with a rifle slung over his shoulder, arm raised and fist clenched in a revolutionary salute. He is wrapped in the pre-1952 national flag of Egypt. Streaming all around him are flags in the Palestinian national colors, hence the caption, “A Million Flags for Palestine.”

His stance and the general composition of the poster quote the now-iconic image of Liberty Leading the People by Delacroix (1830), which memorialized the French revolution, and also The Spirit of '76 by Archibald Willard (1876), which did the same for the American revolution.

pre-1952 national flag of Egypt

By wrapping the figure of the man in the Egyptian national flag of the time (it has been changed several times since 1952), the CPE telegraphed both its solidarity with Palestine and its belief that Palestine was an Egyptian national issue.

It is important to point out that theoretical solidarity with Palestinians, as exemplified by A Million Flags for Palestine, does not always translate into tangible benefits. The history of the Palestinians in Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, and Kuwait should be enough to convince anyone of the unenviable nature of life as a refugee.

It is that aspect that should be emphasized in response to glib Israeli calls for the Palestinians to give up on their demand for the right of return accorded all other refugees and to instead accept perpetual exile in some (any) Arab state. Palestinians have had a variety of relationships, some very good, with various Arab countries, but this is fundamentally irrelevant; those relationships are susceptible to dramatic, unpredictable shifts for reasons having little to do with the Palestinians and everything to do with the internal political dynamics of the country in which they find themselves refugees.

Liberty Leading the People by Eurgene Delacroix

In any event, the original impulse that motivated Egyptians as well as Moroccans, Sudanis, Qataris, Syrians, Algerians as well as citizens of other Arabs nations to express their support for Palestine is not unlike that which drove young men from Minnesota, California, and Maine to join the Union Army and march off to fight a war hundreds of miles away from their homes during the American Civil War (1861-1865). The Americans of 1861 and the Arabs of the post-World War II era had this in common in terms of motivation: something sacred was at stake.

In the Civil War, citizens from all parts of the U.S. suspended and in many cases sacrificed their lives to fight for two principles — initially, saving the Union and later, abolishing slavery. It could be argued that neither of these principles immediately or even directly affected their daily lives. At the outset of the Civil War, Americans did not consider themselves Americans first: rather they considered themselves New Yorkers, Vermonters, or Rhode Islanders first and Americans second. Just as the Civil War shaped an American political identity, so the movement to liberate Palestine has shaped an Arab political identity.

The Spirit of '76 by Archibald Willard

There are other parallels between these two historical moments. In the American Civil War, a central question was secession: whether or not a state (South Carolina) could cease to exist as a state and declare itself a part of a sovereign, independent nation (the Confederate States of America) against the will of the other states in the Union. In the Middle East, the question was irredentism: whether or not an Arab region (Palestine) could cease to exist and in its place be declared an independent Jewish nation (Israel) against the will of the other Arab countries and the entire population of Palestine.

Central to the friction between the Union and the Confederacy was the latter’s notion that the Constitution’s protections, rights, and privileges applied only to the white population. Central to the friction between Arab nations and Israel is the latter’s notion that within its borders Jewish hegemony is ordained, immutable, and perpetual.

In the American Civil War, the Union side was determined to resist South Carolina’s decision to secede for fear that the nation as a whole would collapse. Furthermore, Unionists feared that if unopposed, Southern secession would sandwich the U.S. between a British colony (Canada) to the north and a new, hostile, and unpredictable Anglophile state (the Confederacy) to the south. For similar geopolitical reasons, Arab nations opposed the emergence of a militarily powerful, economically dynamic, and religiously inspired Israel in their midst.

The analogy between the American North’s opposition to the emergence of the Confederacy and the Arab governments unified in their opposition to Israel holds even as regards the curtailment of the press. The Lincoln administration placed some of the strictest limitations on the press in all of American history. Newspapers were shut down, editors arrested, and whole editions confiscated. Censorship was widespread. These are not actions Americans were proud of then or are proud to remember today. Americans revere freedom of expression and were thus relieved when the restrictions were rolled back after the war.

In the Arab world, censorship has a long and varied history. Since 1948, Arab monarchies, dictatorships, and one-party states have had to wrestle with the problem of allowing for public expression of openly revolutionary change in Palestine without fueling similar calls for revolutionary change at home.

The classic method of addressing this problem is censorship. In the case of posters, this means tightly controlling design, printing, and distribution at every step of the process down to the details of public-posting permits.

Several important objectives are accomplished by permitting but also controlling the poster publishing process: (1) the governing authorities can claim to support freedom of expression because posters are “allowed”; (2) the posters provide continued visible support to Arab solidarity with Palestine; (3) the posters create a safety valve through which artists and the public can divert energy; and (4) the posters, with their approved topics and depictions, can serve the agenda of a ruling party or leader. In this sense, Palestine solidarity is a convenient ready-made device with which to manipulate or otherwise distract public opinion and the Arab “street.”

It is interesting to note that the design, production, and distribution of Palestine posters is nowhere uncomplicated. The process is highly controlled in Arab countries; the posters are illegal in Israel; they are outlawed in the Occupied Territories; and they are difficult to exhibit in the U.S.

2003 Liberation Graphics. All Rights Reserved.

Questions for A New

Democratic Discussion

1) How central is Egypt’s role in shaping the contemporary history of Palestine?

2) What is Egypt’s current relationship with Israel?

3) How are U.S.-Egyptian relations influenced by Israeli-Palestinian relations?

Please send us your questions and comments (English only please!)

www.liberationgraphics.com