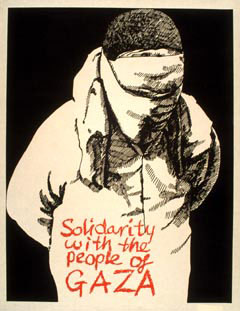

Solidarity With the People of Gaza

Artist: Unattributed

Dimensions: 22” x 18”

Circa 1979

This poster, with its image of a blindfolded and handcuffed Palestinian man, could almost serve as a logo for Gaza. The graphic in this stark pen and ink poster brings to mind the bleak, gritty “cartoon journalism” of Joe Sacco, who wrote a nine comic book series titled Palestine. In volume number six, In the Gaza Strip, he wrote:

Once when I was shuddering at conditions in the Balata camp on the West Bank someone told me, “If you think this is bad, you should see Gaza.”

Source: Fantagraphics Books, 1994

Sacco visited Gaza in the early 1990s; the situation there is exponentially worse now.

It is important to note that the poster expresses

solidarity with the people of Gaza. Sealed off from the rest of the world,

Gaza is a place that most Americans imagine as a black hole, if they think

of it at all. They rarely comprehend it is a place with schools, playgrounds,

hospitals, and neighborhoods all carved out of the barren, sandy moonscape

by hundreds of thousands of people who are guilty of no crime other than

to be born Palestinian. The man in this poster represents the Palestinians

as they believe Israelis would like to see them: silenced, shackled, and

submissive.

Soon after its multiple victories against Egypt, Jordan, and Syria in

the Six-Day War of 1967, the Israeli

government began allowing ultra-nationalistic Israelis to colonize the

territories it had seized in the war, including the 140 square miles of

Gaza, one of the most densely populated areas on the earth. Currently

there are more than 1 million Palestinians in the Gaza Strip: approximately

750,000 refugees and 300,000 indigenous residents. There are also approximately

7,000 Israeli settlers living in seventeen settlements, controlling 30

percent of the land.

Gaza was under the control of Egypt from 1948 to 1967 except when Israel momentarily held it during the ill-conceived British-French-Israeli invasion of the Suez Canal Zone in 1956. When Israel reoccupied Gaza during the Six Day War of 1967, it did not annex it but held onto it to neutralize the territory as an invasion corridor from Egypt. Under the 1978 Camp David Accords, the Sinai was returned to Egypt, but Gaza remained under Israeli control.

Under the 1993 Olso Peace Accords, Israel was to return Gaza to Palestinian control. Those accords imploded in 2000 and Israel now finds itself facing off against a determined and apparently implacable, adversary — Hamas (Arabic: Islamic Resistance Movement), which is based in Gaza.

The initial influx into Gaza of both of Israeli settlers and the IDF

occurred when Egypt was a very real threat to Israel. This is no longer

the case. Now, instead of protecting Israel, the Israeli occupation serves

up a daily ration of dehumanization for Palestinians and a nearly-indescribable,

post-apocalyptic life for the religiously motivated Israeli settlers,

defined by bomb shelters, bullet proof windows, infiltration alerts, armored

convoys, guard towers, walled-in houses and schools, and a general state

of fear. Living conditions for the Palestinians in Gaza are far worse

and even more dangerous, and they respond with an ever-mounting rage that

fuels Hamas.

The ultra-nationalist Israeli obsession with creating and maintaining

settlements in Gaza baffles most Americans, including senior U.S. government

officials. Why would anyone want to raise their children on seized land,

surrounded by the very people from whom it was taken, ringed as it is

with barbed wire, observation posts, and minefields, bristling with machine

gun nests, and requiring around-the-clock protection by some 20,000 Israeli

Defense Force (IDF) soldiers?

According to several recent press accounts, an entire IDF battalion is

deployed to protect fewer than seventy families who live in just one small

Jewish settlement in Gaza, Netzarim. (The IDF does not release figures

regarding the operational size of its units. However, a U.S. military

battalion can be as large as six companies and contain up to 1,000 soldiers

in total). This isolated settlement is a constant flash point that has

generated twelve IDF casualties since the Al Aqsa intifada

began in 2000. It has become a rallying cry for those Israelis, a 59 percent

majority, who believe that Israel should withdraw completely and immediately

from Gaza. (Source: Ma’ariv poll, August 2003).

Military duty in Gaza is so unpalatable to secular Israelis that a growing number of IDF reservists refuse to serve there. Yesh Gvul (Hebrew: There Is A Limit), an Israeli peace organization founded by veterans of Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982, reports that since the outbreak of the second intifadah, more than 500 Israeli veterans and reservists have refused outright to serve anywhere in the Occupied Territories. More than forty of them, including twelve reserve officers, have been sentenced to military prison, usually two weeks to a month, as punishment for this refusal.

For Israel, a nation whose military is modeled on the martial spirit of Yosef Trumpeldor (see Noble to Die), such dissension in the ranks can only be traumatic. Gaza, with its steady drumbeat of gunfire, ambushes, rocket and mortar attacks, and bombings as well as its relentlessly mounting IDF casualties, has become the Israeli equivalent of the “Russian Front” of World War II — the place German soldiers feared to go more than any other because of its hopelessness and horror.

News of Israeli assassinations, raids, arrests, helicopter gunship attacks, and house demolitions is instantaneous and globally disseminated by Al Jazeera, (Arabic: the Peninsula), the Arab world’s main satellite news network. This round-the-clock, up-front-and-personal coverage makes the Israeli occupation of Gaza and the West Bank a daily feature of television and press reportage throughout the Arab world.

The devolution of the triumphalist Israeli vision of Gaza as a sanitized, neutral corridor into a deadly quagmire is a perfect example of New York Times Middle East correspondent Thomas L. Friedman’s “iron law”:

If there is one iron law that has shaped the history of Arab-Israeli relations, it’s the law of unintended consequences. For instance, Israel is still wrestling with all the unintended consequences of its victory in 1967.

Source: “One Wall, One Man, One Vote,” New York Times, 14 September 2003

Most Israelis want to withdraw from Gaza, immediately, unconditionally,

and permanently. However, Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon refuses

to even consider doing so, at least partially, because for Israel to leave

without securing some political or negotiating advantage would appear

to be a tactical retreat. Above all else, he fears a reenactment of Israel’s

loss of face when it withdrew unilaterally from southern Lebanon in 2000.

Sharon also does not want to alienate Israel’s small yet powerful settler movement. The religiously driven determination of these settlers to impose their presence in Gaza is caught in the words of one of Netzarim’s inhabitants:

God sent me here to live, and I know what I need to do to keep myself and my family safe. I think this place is so important, with or without the people. It’s important to control Gaza so terrorism can’t get into Israel…. Books show that since Abraham’s time, this [land] belongs to us.

Source: “In Gaza, Citadel to Some, Island to Others,” Washington Post, November 3, 2003

Many credible religious scholars report that there is little archeological evidence of a significant Jewish presence in Gaza during biblical times. Yet Israel’s ultra-Orthodox settler movement dismisses such evidence and has fused its millennium fervor with phenomenal political clout in the Knesset, the Israeli parliament. The result is rending the fabric of life for both Palestinians and Israelis.

Nowhere is this rending more visible than in the barrier that surrounds Gaza and a new one being constructed around the West Bank. Stretching thirty-two miles with numerous watchtowers, the fence around Gaza is constantly and intensely patrolled by units of the IDF. The Israeli government claims that this fence is a success because it prevents Palestinian attackers from entering Israel, though this is debatable. It is now being emulated by a similar but exponentially larger barrier snaking its way around and into the West Bank. Construction of this massive, 400-mile long concrete structure has decimated Palestinian villages and agricultural fields in its path. The estimated cost is staggering: approximately $1.6 million per mile.

In yet another example of how the Palestinian-Israeli conflict generates its own lexicon, Israel’s supporters call it a “security fence,” a “separation fence,” or a “security barrier.” Its detractors call it an “apartheid wall,” a “Wall,” or the “New Berlin Wall.”

Ironically, the Israeli “security fence” has Israeli populations located on both sides — Israelis in Israel proper on one side and Israeli settlers living in Jewish settlements in the West Bank and Gaza, on the other.

Many Palestinians and international groups fear that the new Israeli security fence will become a de facto border between Israel and an envisioned Palestinian state, even though Israel claims that fences are by definition not permanent. Many Americans — Israel advocates among them —are openly opposed to the barriers. And yet a series of presidential administrations and Congresses have been singularly ineffectual in applying any meaningful U.S. pressure against them.

© 2003 Liberation Graphics. All Rights Reserved.

Questions for A New

Democratic Discussion

1) Given that Gaza is a miserable place to live, why do the indigenous Palestinians not leave and make a home elsewhere? Why do the refugee Palestinians not leave to become refugees somewhere else? Why do the settlers not leave to settle elsewhere?

2) The Israel solidarity movement in the U.S. claims it was never Israel’s intention to create a seething mass of anti-Israeli Palestinians in Gaza. What went wrong in terms of Israeli’s analysis and strategy? What current Israeli policies might evolve in similarly unintended ways?

3) History is replete with examples of governments building

walls to either keep people in or out:

-The Great Wall of China (between Jiayu Pass in the west and the mouth

of the Yalu River in the east.)

- Hadrian’s Wall (between present-day England and Scotland)

- The Berlin Wall (between Communist East Berlin and Allied-controlled

West Berlin)

- The Long Walls of Greece (between Piraeus and Athens)

- France’s Maginot Line (along the borders with Belgium, the Netherlands,

and Germany)

- The Atlantic Wall of the Third Reich (from northern Norway to the Franco-Spanish

border)

Most of these examples, though state-of-the-art engineering feats in their time, are today looked upon as laughable follies in terms of how well they served their intended purposes. How might Israel’s walls be seen in the future — as astute policy, insane folly, or something in between?

5) Much of the controversy over Israel’s new barrier is semantic. In what ways has the Palestinian-Israeli conflict been a contest over language? What are other examples of word games this conflict has generated?

Please send us your questions and comments (English only please!)

www.liberationgraphics.com