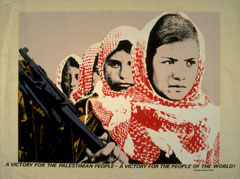

A Victory for the Palestinian People...

Artist: Unattributed

Publisher: Single Spark Films (Revolutionary Communist Party, USA)

Dimensions: 20” x 26”

1973

This silk-screened poster was created to promote a movie entitled We Are the Palestinian People, which was one of a series made by Single Spark Films, the now-defunct film unit of the Revolutionary Communist Party, USA (RCP). The graphic features four armed, kaffiyeh-clad women marching in a line and the caption “A Victory for the Palestinian People... A Victory for the People of the World.”

The other movies in the Single Spark Films series were:

Off the Pig (1968) 20 minutes

Mayday! (1969) 15 minutes

On Strike (1969) 25 minutes

People’s Park (1969) 25 minutes

Pig Power (Late 1960’s) 6 minutes

Only the Beginning (1971) 20 minutes

Winter Soldier (1971) 20 minutes

Breaking with Old Ideas (1975) 120 minutes

Mao Tse-Tung, The Greatest Revolutionary of Our Time (1978) 17

minutes

Source: Canyon Cinema website

As can be adduced from the titles, these films embodied a very distinct political perspective. At the time this poster was printed, the U.S. was in the midst of a chaotic social upheaval stemming from the convergence of: the Civil Rights movement; a broad domestic resistance to the Vietnam War (1964-1975); and a vast counter-culture epitomized by the epic music concert in Woodstock, New York (1969).

There are two significant features of this poster that may not be apparent to the casual observer. First, this poster marks one of the earliest appearances of the Palestine liberation movement in American popular culture. At the very least, We Are the Palestinian People is one of the first or the first American-produced film on Palestine. Second, this film had a marginal impact given that it was produced by the Revolutionary Communist Party, USA, which was then and still is on the outermost fringes of political legitimacy. These two features establish this poster as the initiation point of an arc marking Palestine’s progress through the American cultural landscape.

We Are the Palestinian People is overtly pro-Palestinian and it cannot claim to be representative of anything except the RCP’s monotonously anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist, and anti-American bombast. It does, however, offer a departure point from which to examine how subsequent efforts to present Palestinian culture have fared in the U.S. since 1973. This particular film failed to reach a wide audience for several reasons, not least of which is the creative, technical, and political marginality of its producers. But many other Palestinian cultural products have faced real challenges to distribution based not on their content but rather on their potential to change American public opinion. For example:

- In 1983, an exhibit of Palestinian posters at the U.N.’s headquarters

in New York, which contained several Israeli-produced posters, was shut

down after one day after the Israeli delegate complained that the U.N.

did not follow guidelines for exhibits. (In the interest of full disclosure,

it is noted here that this exhibit was curated by Liberation Graphics.)

Source: “Outcry Shuts Palestinian Poster Show at U.N.,”

New York Times, August 21, 1983

- In 1989, the New York Shakespeare Festival cancelled its invitation

to the El Hakawati Palestinian Theatre Company, which was scheduled

to perform The Story of Kufur Shamma. The festival’s

producer, the late Joseph Papp, said, “I never objected to the

play itself. After I agreed to present the play I discovered that we

were not putting on anything else [about the Israeli-Palestinian problem]

at the same time.” Source: “Palestinian Play Cancelled,”

Washington Post, July 26, 1989

- In 2002, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS)

announced that Palestinian filmmaker Elia Suleiman’s dark comedy

Divine Intervention, which had recently won both the Jury Award

the Fipresci Award at the Cannes Film Festival, was ineligible for Oscar

considerations for the category of Best Foreign Film because Palestine

is not a country recognized by its rules. This decision was roundly

criticized because the Academy had previously accepted entries from

Taiwan, Wales, and Hong Kong, none of which are countries recognized

by the U.N. Furthermore, Palestine has had Permanent Observer status

at the United Nations since 1974 and is diplomatically recognized by

many countries. Source: “Oscar Escapes Mideast Dispute,”

Toronto Star, December 9, 2002 and the Electronic Intifada

website.

- On February 20, 2002, director James Longley’s film Gaza

Strip was screened by Columbia University’s School of International

Public Affairs (SIPA) Middle East Working Group. A Jewish student group

protested in an effort to block the screening. When this failed, the

group demanded that a pro-Israel film be aired in conjunction with Gaza

Strip, citing the need for balance when discussing the Palestinian-Israeli

conflict. Source: “Gaza Strip Screening Sparks Debate,”

Communiqué (Newspaper of the Columbia University School

of International Public Affairs), March 6, 2002

- In 2003, A Little Piece of Ground, a book about three twelve-year-old

Palestinian boys living in the Israeli Occupied Territories and written

by acclaimed English author Elizabeth Laird, ignited a transcontinental

controversy involving the British publisher, Macmillan Children’s

Books (which defended the book), Canada’s largest children’s

bookstore Kids Books of Vancouver (which refused to carry the book),

and American Jewish organizations, including Jewish Book World (which

criticized the book for its failure to provide “political context”).

Source: “Controversy Over Children’s Book A Little Piece

of Ground,” National Public Radio (NPR) interview, September

30, 2002.

- On September 12, 2003, Rutgers University officials, citing concerns over logistics, withdrew permission for the Third National Student Conference of the Palestine Solidarity Movement to be held on campus. “Israel Inspires,” a counter-conference scheduled on campus for the same weekend (October 10-12) and sponsored by Rutgers Hillel and the American-Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), had the support of the school’s president, Robert McCormack. McCormack said, “The governor and I agreed that we find the views of New Jersey Solidarity to be reprehensible. But we also agreed that the best way to counter deplorable arguments is more discussion, not less, and that the appropriate place for this kind of discourse is the university. Governor McGreevey and I share the belief that the strength of our society depends on such openness.” The Palestine solidarity conference was relocated to a local hotel; however, the university approved a concurrent on-campus Palestine solidarity rally. Sources: “Rutgers University Officials Cancel Palestine Conference,” Hammerhard MediaWorks, September 12, 2003; Israel Inspires web site and New Jersey Solidarity web site.

Considered individually these closings, cancellations, ineligibility rulings, and book boycotts would be reason enough for Americans to be concerned about their ability to see posters, attend plays, read books, review films, or discuss topics that focus on Palestinian perspectives. Ironically, all these Palestinian creative resources were, or are, freely available in most countries of the world including Israel, but not in the U.S.

When considered collectively, they suggest a pattern of reflexive domestic opposition to the presentation of Palestinian culture in the U.S.

There are three troubling, recurrent features to these controversies. First, the opposition does not spring from mainstream sources but rather originates from special interest groups. Second, those groups readily resort to technical or bureaucratic justifications to block or cancel a presentation. Third, and perhaps most unfortunate, the opposition is motivated by the sense that these cultural presentations are incitements and threats that must be defended against.

Most Americans do not consider cultural endeavors to be negative, dangerous activities even if they do not themselves care for the content or support the point of view being put forward. Though in the short run these blockading efforts have succeeded in canceling a play here and banning a book there, the real long-term effect, ironically, is to widen the gap between American Zionism and grassroots America. That such a gap already exists is proven by the fact that in many, though not all, of these incidents, alternative venues have materialized, thereby allowing the cultural presentations to go on as planned.

It would appear that the intentions of the Israel advocacy movement are to elevate everything that reflects well on Israel and to denigrate everything that could possibly reflect well on Palestine: in other words, to maintain a stereotype of the Palestinians as wanton, irrational, hateful, and backwards. This approach is what is known in theatre parlance as a “forced perspective” — the tightly controlled use of props, distorted imagery, false horizons, outsized sets, angled seating, and other technical manipulations which force the viewer into a relationship with the space that would not occur naturally. The main difference is that in the theatrical environment the audience is prepared, even willing, to suspend its sense of reality. In real life, however, they are not.

When efforts are made to expose Americans to the Palestinian perspective, Israel advocates frequently respond in a way that is more akin to the rules of Israeli military occupation than to Judaism’s cherished ethical principles or its ancient respect for the arts. Israel’s infamous Military Order 101 offers some insight:

Military Order 101 of 27 August 1967

Order Concerning Prohibition of Incitement and Hostile Propaganda

It is forbidden to conduct a protest march or meeting (grouping of ten or more where the subject concerns or relates to politics) without permission from the Military Commander. It is also forbidden to raise the flag or other symbols, to distribute or publish political articles and pictures with political connotations. No attempt should be made to influence public opinion in a way which would be detrimental to public order/security. Censorship regulations are in accordance with the Defence Regulations (Emergency) 1945. The punishment for non-compliance is a prison sentence of up to 10 years and/or a fine of 2,000 Israeli lira; soldiers may use force to apply this law.

While it is important for Americans to be aware of the contrast between the vibrant artistic traditions that flourish inside Israel and the dramatic curtailment of free expression imposed in the Occupied Territories, perhaps a better model of conflict between censorship and artistic freedom is found much closer to home: in the vociferous antebellum battle over the publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Written in 1852 by Harriet Beecher Stowe, this novel sympathetically depicts the life of a slave in the American South. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was immediately banned by all the states that eventually constituted the Confederacy. U.S. postmasters were obliged to destroy all copies on arrival in Southern post offices. Bookstores and libraries were searched and purged.

The American South (and also Tsarist Russia, which likewise banned Uncle Tom’s Cabin) objected to the book not because it depicted a slave but because it suggested the notion of equality. The central goal of its efforts to censor Uncle Tom’s Cabin was to prevent the legitimization in the North of the concepts of slavery as morally repugnant and opposition to it as just. In this sense, this history is a direct parallel with the efforts of the hasbara (Hebrew: Israel advocacy; solidarity) movement in the U.S., which has as its goal to prevent the legitimization of a perspective that sees Zionism as morally indefensible and opposition to it a moral imperative.

© 2003 Liberation Graphics. All Rights Reserved.Questions for A New

Democratic Discussion

1) Is “balance” required in every cultural product or presentation? To what extent should “balance” be provided in any artistic work having to do with Israel or Palestine?

2) What does it say about the values of the hasbara

movement that it is willing to be identified with the closing of plays

and banning of books?

3) How does the history of American Jewish writers, actors, playwrights,

singers, and dancers, and other artists who courageously confronted McCarthyism

in the 1950’s contrast with contemporary hasbara efforts

to suppress artistic expression?

4) When Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published in 1852, the American South’s angry and vitriolic response helped to boost sales of the book to record levels. What explains this reaction? How do Americans typically respond to being told that they cannot or should not see a thing? To what extent might the actions of the Israel advocacy movement be, at its core, counterproductive? If so, what might be a better strategy for it to adopt?

5) Has the U.S. Palestinian solidarity movement ever attempted to shut down a pro-Israel play or ban a pro-Israeli book? If not, why? If yes, what were the circumstances and results?

6) Mainstream Americans once expressed open cultural solidarity with Israel. For example, the famous “blue box” fund-raising program of the Jewish National Fund (JNF) raised millions of dollars for Israel and created positive discussion of Israel in millions of American homes and schools. What happened to that mainstream support? Is there anything like that happening today in the U.S.? If yes, what specifically? If no, what explains the loss of this important expression of support for Israel?

Please send us your questions and comments (English only please!)

www.liberationgraphics.com