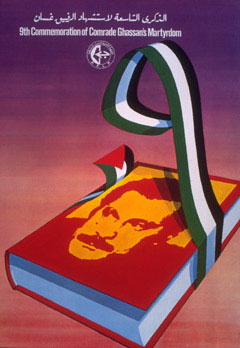

Ninth Commemoration of Comrade

Ghassan’s Martyrdom

Artist: Marc Rudin (Switzerland)

Dimensions: 20” x 30”

Publisher: Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP)

1981

Ghassan Kanafani was a renowned Palestinian novelist, short story writer, dramatist, journalist, and artist. In this poster, his portrait appears on the cover of a book wrapped in a ribbon made of the colors of the Palestinian flag. The book represents Kanafani’s contribution to contemporary Palestinian literature. The looping ribbon, caught in the shape of the number nine, reminds Palestinians of the years since his death.

The poster leads the eye from a dark background, signifying bereavement, into a foreground that washes the book in a bright and optimistic light, signifying that his legacy survives. The predominant color in the poster is red, referencing Kanafani’s membership in the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), a Marxist political faction.

Kanafani was born in ckra, Palestine during the British Mandate. During the first Arab-Israeli war of 1948, when he was twelve, he fled with his family to Lebanon and then to Syria. Much of his literary output centered on the experiences of exile, loss, and nationalist struggle.

Kanafani was assassinated via car bomb in Beirut on July 8, 1972. He was thirty-six years old. Also killed in the blast was his niece Lamise, age seventeen. At the time of his death Kanafani was the editor of the weekly newspaper of the PFLP, Al Hadaf (Arabic: The Target). Several weeks earlier, the PFLP had taken credit for a bombing carried out by three Japanese Red Army guerrillas in Israel in which twenty-six Israelis were killed.

Kanafani’s writings include The Land of the Sad Oranges, Return to Haifa, Sa’d’s Mother, The Death of Bed No. 12, The Slave Fort, and many others that are still in print and widely read around the world. His first novel, Men in the Sun, was adapted by the Egyptian director Tawfiq Salim into a film, Al-Makhduun (Arabic: The Deceived) that was banned in several Arab countries owing to its transparent references to the failure of Arab regimes to address the question of Palestine. The plot features three men seeking escape to Kuwait who become trapped inside a water truck in the desert. Each of the men is of a different Palestinian generation; ultimately, all three perish because the handles to the hatch are on the outside and they don't cry for help.

(An eerily similar story with Jewish characters unfolds in Andrzej Wadja’s 1956 film, Kanal, based on a story by Jerzy Stawinski. Three leaders in Warsaw’s Jewish resistance seek escape, with a band of comrades, through the city’s underground sewers. At the end of the film, two of the characters reach the light where the sewer leads above ground, but a grate bars their exit and they lie helpless, awaiting their doom.)

Less than a year after Kanafani’s assassination, a courageous Israeli reporter, Raphael Rothstein, writing for Ha’aretz, revealed in an article titled “Undercover Terror: The Other Middle East War,” that Kanafani’s assassination took place under Operation God’s Wrath. This was an Israeli campaign, mobilized during the tenure of Prime Minister Golda Meir, to decapitate the Palestinian political leadership in the belief that this would result in the collapse of Palestinian resistance to Israel.

Kanafani was an easy target. He had no special protection and was not living undercover. He was a noncombatant; his status as PFLP spokesperson derived exclusively from his capacities as a writer. The assassination of Kanafani was meant to send the message that no Palestinian, anywhere, would be safely out of reach of Israel’s vaunted intelligence and security networks.

The Israeli policy embodied in Operation God’s Wrath proved morally repugnant to the international community. Furthermore, it accomplished nothing in terms of deterring the Palestinians from pursuing their goal of national liberation or making Israel a safer place to live. Indeed, it can be argued that Israel’s “iron fist” policies have been an unqualified disaster, leading Palestinians to ever more desperate means of resistance such as suicide bombings, the isolation of Palestinian moderates, a turn to radical Islamic fundamentalism, the emergence of Hamas as a political and military force, and the devolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict into what U.S. military strategists term “low intensity warfare.”

This mode of combat does not have the potential to destroy Israel’s armed forces or even, in the short term, its economy. However, it can thwart Israel’s goal of being a regional tourism, manufacturing, financial, trading, and commercial center. It is ideal for discouraging foreign investment, decreasing new Jewish immigration, accelerating Israeli emigration, draining Israel psychologically, and demoralizing Israel’s few international allies.

Former Israeli Prime Minister Yitzak Rabin recognized the futility of Israel fighting a low-intensity war. He understood that though Israel could strike back repeatedly and mercilessly, it would be at the cost of Israel’s soul. For this reason he agreed to make peace with the Palestinians and for this very reason he was, in turn, assassinated in 1995 by an ultra-nationalist Israeli. Rabin’s death validated the message of Operation God’s Wrath: truly, no one is safe.

The current Israeli government of Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, who vehemently opposed the Oslo Peace Accords, has reverted to an open assassination policy such as that which targeted Kanafani back in 1972. The Sharon administration refers to this as “targeted killings,” believing, perhaps, that this wordplay renders the underlying principles more palatable to the sensibilities of the Israeli people and to the U.S. government, which has itself re-introduced a limited assassination policy in its “war on terror.”

The effects of this lamentable policy is to trap Israel in a vicious double-bind: the more Palestinian leaders it assassinates, detains, or exiles, the more the Palestinian underground is decentralized, putting it farther and farther away from any organized political control under the Palestine Authority.

As Sharon pursues his vision of a “Greater Israel,” he moves the Palestinian-Israeli conflict towards a contemporary re-enactment of The Battle of Algiers. During France's bitter Algerian War (1954-62) it engaged in desperate, zero-sum combat with the indigenous Algerian Front de Libération Nationale or FLN (French: National Liberation Front), which was determined to overthrow the French occupation regime. This gritty, house-to-house confrontation is brilliantly depicted in director Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1965 movie classic of the same name.

In the Algerian struggle, revolutionaries organized into small cells, each of which had very little information on the whereabouts or doings of other cells. This denied French forces the opportunity to bag large quantities of arms or explosives. It also meant that the death of any individual operative or the capture of any cell would not impede the FLN’s strategic plan for ending the French occupation of Algeria.

Israeli apologists bridle at the comparison with a colonial regime. However, Sharon’s aggressive strategy towards Hamas and the other Palestinian militias incorporates the identical strategic flaw as that of the French: it fails to see that the Palestinian uprising is a nationalist movement, not merely an anti-colonial one. As such all Palestinians are engaged and all Palestinians embody, to a greater or lesser extent, the same kind of commitments depicted by Ali le Pointe, the Algerian revolutionary and protagonist of The Battle of Algiers, who allows himself to be sacrificed rather then fall into the hands of the French.

Shortly after his death, Kanafani’s Danish wife, Anni, together with friends and family, established the Ghassan Kanafani Cultural Foundation, which operates a series of kindergartens, centers for children with disabilities, and public libraries in Palestinian refugee camps across Lebanon. She remained in Lebanon and raised her two children as Palestinians. She says that she would have raised her children the way she did whether or not Ghassan had been killed.

Ghassan Kanafani was born on April 9, the same date as the 1948 Deir

Yassin massacre of Palestinian civilians by Israeli forces. Kanafani himself

never celebrated his birthday for that reason. April 9 is a national day

of remembrance for Palestinians everywhere. As a mark of enduring respect,

each year on July 9, Ghassan Kanafani and his niece Lamis are commemorated

in many Arab countries and abroad.

© 2003 Liberation Graphics. All Rights Reserved.

Questions for A New

Democratic Discussion

1) Assume that Kanafani is alive today to write a sequel to Men in the Sun, based on the evolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict since 1972. Assume further that in this sequel the three characters thrown together are an Israeli, a Palestinian, and an American. What metaphorical situation do you propose for these characters? Are they helpless to escape, like the men of the first novel, or is there a way out of their deathly predicament?

2) What is the role of the artist and the journalist in a revolution? Do artists and journalists enjoy any special, internationally recognized protections?

3) What comparisons can be made between Ghassan Kanafani and other assassinated artists? Consider for example:

- Garcia Lorca, the poet murdered by the Nationalists at the start of the Spanish civil war.

- Victor Jara, the Chilean singer who, because of his association with the Partido Popular (Spanish: People’s Party) was murdered by the regime of General Augosto Pinochet.

- Ken Saro-Wiwa, the Nigerian novelist and children’s book author who was executed by a secret tribunal in 1995 because of his association with the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People.

4) The poster refers to Kanafani as a martyr. What is a martyr? Who decides who has become a martyr? What purposes does martyrdom serve? How does martyrdom of an assassinated figure affect the assassinating party?

5) To what extent have political assassinations in the United States — Abraham Lincoln; Malcolm X; John Fitzgerald Kennedy; Martin Luther King, Jr.; Robert Kennedy — succeeded in destroying the ideals each man stood for?

6) Prime Minister Yitzak Rabin was assassinated in 1995 by an ultra-orthodox Israeli who believed that Rabin’s acceptance of the Oslo Peace Accords was a threat to Israel. Was it? Is Israel less or more threatened today?

Related Work

General Union of Palestinian Women

Please send us your questions and comments (English only please!)

www.liberationgraphics.com