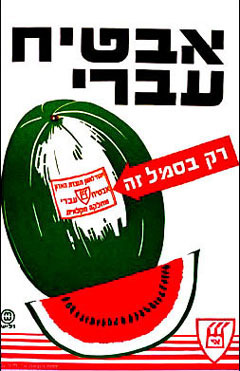

Buy Hebrew

Watermelons

Artist: Unattributed (Israel)

Circa 1930

The Hebrew caption on this poster reads, “Buy Hebrew Watermelons.” A seemingly innocuous fruit advertisement, the poster is evidence that even during the yishuv (Hebrew: community) period, approximately 1918 to 1948, friction was building in Palestine between the newly arrived Jewish immigrants and the indigenous Palestinians.

The caption for this poster currently at the website of the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) reads as follows:

Farm products of the Jewish settlements in the Land of Israel were pitted in a stubborn struggle against fresh produce from local Arabs and neighboring countries. The very existence of the Jewish settlements’ agriculture and industry was at stake. Watermelons were one of the fruits that needed protection against foreign products.

Source: “Images of A State in the Making,” Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs website

Ironically, the word “foreign” is used to describe the produce

of the indigenous Palestinian farmers. Indeed, for centuries prior to

the arrival of Zionist halutzim (Hebrew: pioneers), Palestinians

had been growing vegetables, fruit, grains, and legumes and all manner

of crops in what is present-day Israel. Significant competition from Jewish

farmers arose only after enterprises such as the Jewish

National Fund (JNF), succeeded in acquiring land in Palestine on which

to establish kibbutzim (Hebrew: collective settlements).

The history of these land transactions remains highly controversial. Zionist historians claim that purchases were above-board and transparent. Palestinian historians claim that they were made between agents of the JNF and absentee landlords, Turkish Ottoman officials, and others who were not the actual residents and who did not have the legal authority to sell land to foreign agents. These historians also assert that land was sold by Palestinians who did not understand that the JNF was making stealth purchases as part of an irredentist movement to reclaim the ancient Jewish homeland. Some evidence for these claims come from Theodor Herzl himself, who in 1895 recorded in his diary his vision of how land would be acquired:

We must expropriate gently the private property on the state assigned to us. We shall try to spirit the penniless population across the border by procuring employment for it in the transit countries, while denying it employment in our country. The property owners will come over to our side. Both the process of expropriation and the removal of the poor must be carried out discretely and circumspectly. Let the owners of the immoveable property believe that they are cheating us, selling us things for more than they are worth. But we are not going to sell them anything back.

Source: Mulhall, John W. America and The Founding Of Israel: An Investigation of America’s Role. Deshon Press, 1995, p. 49. Also in Morris, Benny. Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881-2001. Alfred A. Knopf, 1999, pp. 21-22.

To this day, the sale of land by Palestinians to non-Palestinians or by Israelis to non-Israelis is considered an unforgivable betrayal of their respective national values.

Zionist strategists envisioned its brand-loyalty campaign for kibbutzim produce as a way to involve local and international sympathizers in the struggle to build the new Jewish state. What was missing from their strategic plan was any consideration of the effect this market-shifting approach would have on the Palestinians. The great success of kibbutzim agriculture at first damaged, and then decimated, Palestinian markets. Predictably, the Palestinians came to see the influx of Jewish settlers not as a boon to the economy but as a threat, and they began to oppose it.

For the Palestinians, the Zionist produce campaign was an ominous harbinger of things to come. It parallels what occurred during the settlement of the American west: “pioneers” succeeded in clearing the land of unwanted native populations in large part by destroying the grasslands and buffalo herds, which had been a primary source of food, clothing, medicine, tools, trade items, and other necessities.

The rustic and primitive kibbutzim of the 1930s have evolved into a vibrant and diverse economic engine that now accounts for a major share of Israel’s agricultural output as well as a significant portion of the country’s light and medium industrial production. Not surprisingly, Palestinian domestic agricultural productivity has declined dramatically.

Thus the central educational lesson of this poster is that the contemporary Palestinian-Israeli conflict is not now, and never has been, a primarily religious conflict. Rather, it is a conflict about the land: who will control it, who will live on it, what will be grown on it, who will work it, and who will benefit from its productivity. In the hyper-politicized atmosphere attended by Zionism, even the most mundane aspects of life, such as the purchase of a watermelon, are radically politicized and woven into the fabric of Israel’s complex existential struggle.

© 2003 Liberation Graphics. All Rights Reserved.

Questions for A New

Democratic Discussion

1) Could the early Zionists have worked cooperatively with local Palestinian growers to expand and develop the potential of the land together? Were there Zionists dedicated to cooperation with the indigenous Palestinians?

2) There are a growing number of “Boycott Israel” movements in Western Europe and the United States. What are the intentions of these movements and what relationship do they have to the early branding campaigns for kibbutz-grown produce?

3) Many Israeli-run farms and agricultural collectives

employ Palestinians as laborers. However, an increasing number employ

workers from such places as Romania, Thailand, and the Philippines. Why

would Israeli producers hire workers from distant lands rather then local

Palestinians?

Please send us your questions and comments (English only please!)

www.liberationgraphics.com